William Alsop

The British architect William Alsop

would like to see a project from his office, as for instance The Fourth

Grace in Liverpool, as a “[…] form-less building that appears to be out

of focus and always moving.”3

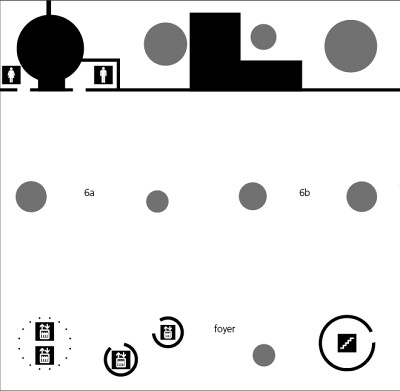

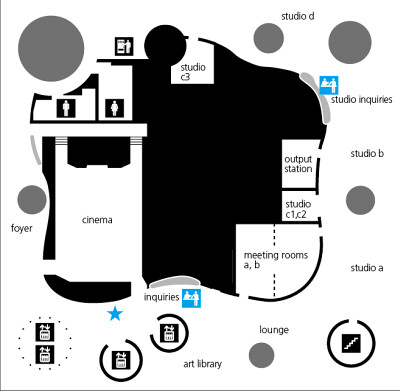

The work of William Alsop and Erick van Egeraat overlaps

significantly here. The design of William Alsop for the Fourth Grace in

Liverpool resembles the design of Erick van Egeraat for Capital City in

Moscow. In the Netherlands both architects have not by coincidence

designed a pop-podium that looks like a boulder – Erick van Egeraat

designed the Mezz in Breda, William Alsop designed the Muzinq in Almere.

There are of course also lots of differences. William Alsop is a

painter, and he works this attitude out in his architecture in a very

explicit manner, for instance in his articulate coloring. But despite

the differences between them here the overlap in architectural concept

is relevant and informative.

The notion of the ‘formless, out-of-focus’ building of William Alsop

is connected with the ‘soft’ architecture of Erick van Egeraat. In the

eyes of Erick van Egeraat Modernism is too simple and too easy legible.

Baroque buildings are far more interesting, because they are much less

legible, and therefore don’t bore that easily.

Erick van Egeraat - Capital City, Moscow (Copyright EEA)

William Alsop - Fourth Grace, Liverpool

I think that the amount of recoding4, the amount of expression, the

Baroque-ness in the architecture of William Alsop and Erick van Egeraat

makes both architectures not easily legible, and therefore leaves the

spectator puzzling sometime about what they see. The decoration

provides a ‘suspense’, just as film and television leave you wondering,

suspended, about how this film or series will end. And is ‘suspense’

not one of the most powerful emotions that one can experience?

William Alsop and Erick van Egeraat are not alone in their

realization of suspense. The work of modern artists like David

Lachapelle and Jasper Goodall shows the same kind of insistence on the

form-less, the surreal, the decorated, the Baroque.

The work of these Baroque architects and artists find their

conceptual image in the artwork ‘the Manimal.’5 This is a

computer-generated hybrid of a snake, a lion and a human. The multitude

of differences in comparison to a human face and the stratification of

the image of the Manimal produces a ‘suspense’ with the spectator.

Erick van Egeraat: “Often we find things that we don’t understand beautiful.”2

Feminine beauty

Interesting is that the work of Jasper Goodall, David

Lachapelle and Erick van Egeraat also overlaps on an other level. All

three have a fascination for the female (sexual) object and claim that

they make things that in the first place just have to be ‘beautiful.’

The work of Goodall and Lachapelle is explicit erotic. In the work of

Erick van Egeraat feminine beauty plays a more implicit a role. (Erick

van Egeraat’s wife is not by coincidence a model.)

Erick van Egeraat states that you can describe (feminine) beauty in

ideal measurements and proportions. But in reverse it is never true

that if you apply these ideal proportions, a design automatically

becomes beautiful. Just look at the ‘ideal’ women that are generated

with the computer. Apparently beauty is more complex and maybe

imperfections and coincidences are also important.

According to Erick van Egeraat Le Corbusier developed his Modulor so

his associates could no longer mess things up with this

measurement-system. But not a single building by Le Corbusier follows

his system totally. Clearly Le Corbusier knew that beauty doesn’t

emerge from ideal measures.2

The question that arises with the work of Jasper Goodall, David

Lachapelle, and Erick van Egeraat is whether design that is stripped

from every ideology necessarily focuses again on the natural, and in

extension of that on the female (sexual) object. If you strive like

them to a layered beauty that develops itself from a desire, a

suspense, than the desirable female object seems to be the perfect

starting point.

This article has been published in Dutch in the architectural magazine Pantheon// in July 2006.

1. This citation is an excerpt of an interview with Erick van

Egeraat that I did with Barbara Luns in February 2004 and that has been

published in Pantheon//.

2. Egeraat, Erick van; The Value of Beauty, lecture in Bacinol 12 January 2006

3. Jencks, Charles; The Iconic Building, Frances Lincoln, London 2005

4. Raaij, Michiel van, Remix Mies, Pantheon// Projective Landscape, February 2006

5. Berkel, Ben van; Bos, Caroline; Move, UN Studio, Amsterdam 1999

Update 3 march 2007

William Alsop announced

this week that it will built a 43-story appartment-tower in the center

of London. On top of a public plinth 15 stories of self-storage spaces

are hidden behind an artwork of Bruce McLean. More similar to the Avant-Garde project in Moscow of Erick van Egeraat than I could have ever imagined.

I don’t know why the design by Alsop uses so much dark colors, that

way avoiding a contextual relationship with the sky. Maybe architects

should ‘paint’ more on white canvasses when designing towers.

William Alsop - 151 City Road, London